The Monitor is a weekly column devoted to everything happening in the WIRED world of culture, from movies to memes, TV to Twitter.

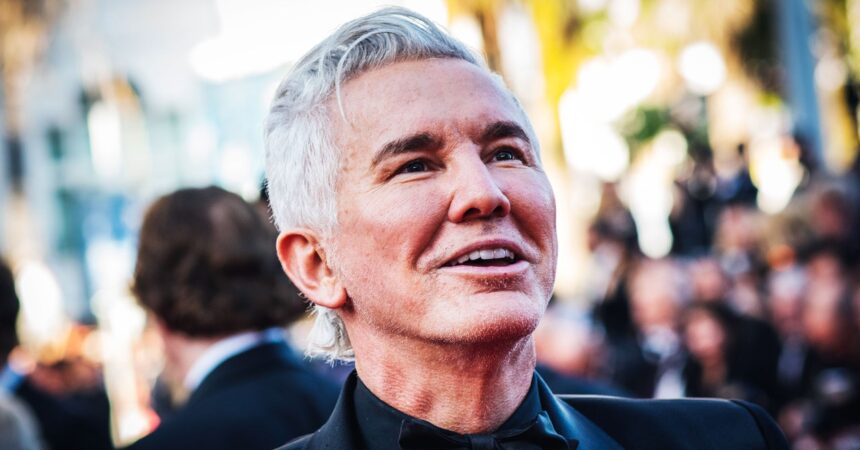

Baz Luhrmann blends in well here. The Australian writer, director, and producer is known for his flashy, hyper-realistic style, and on this particular New York night he’s in a sparse, brightly lit former taxi warehouse in Chelsea, talking to a robot. The bot’s name is Ai-Da; she’s a painter powered by artificial intelligence. (Yes, she identifies as female.) Before Luhrmann took the stage next to her, she was doing a watercolor while people gawked and took photos. “Did you see Elvis, Ai-Da?” he asked. She paused for an almost awkward period before replying. Her favorite Luhrmann film is Romeo + Juliet.

The director was unfazed. “I am not fearful of AI,” Luhrmann told me prior to the presentation, which he gave as part of the opening of a new art installation called Saw This, Made This. Then he backpedaled a bit, clarifying that he’s not fearful of AI taking his job as a director. “I spoke to Ai-Da this morning and said, ‘Should we be concerned about AI destroying the world?’ and she said, ‘Absolutely.’” Ultimately, Luhrmann says, AI is a new technology, and how it will be used—for creative purposes or nefarious ones—depends on humans.

Pretty much every writer, director, musician, and painter is facing the AI question right now. Many answers echo Luhrmann’s. It depends on their interactions with the technology. Members of the Writers Guild of America, who are currently on strike, are concerned that studios may one day soon want AI to write scripts that human writers then fix for a lower fee. Frank Ocean fans are reportedly getting scammed into paying for machine-generated songs. Visual artists claim AI models are unfairly being trained on their work. This week, author Stephen Marche released a novella he wrote with considerable help from large language model (LLM) tools ChatGPT, Sudowrite, and Cohere.

The outcome of these conflicts over AI use in pop culture will have ramifications for decades to come. That’s why the arguments are so heated. Tech has been evolving and, forgive me, disrupting things for long enough now that people know the signs. Without some shared laws, beliefs, and ethics to govern the ways AI can be used, it could run rampant. Without the guidelines currently employed by the US Copyright Office stipulating that copyrightable works must have human authorship, without rules about what jobs AI can do, chaos reigns.

Ironically, chaos is what Luhrmann notes that humans can handle and AI can’t. “Artists, to a person, are generally self-medicating flaws and chaos within them,” he says. “The thing AI just doesn’t have at the center of it is random chaos. Emotion.” I note the sign seen on the WGA picket line that said “ChatGPT doesn’t have childhood trauma.” The director agrees. “There’s understandable fear,” he says, “because when you get this massive change, there’s going to be things caught in the crossfire.”

That doesn’t mean he thinks AI can replace human creativity, at least not presently. Which brings us back to Elvis Presley. There are people who change their appearance, their bodies, their mannerisms in order to perform as the King of Rock ’n Roll. They’re called impersonators. In his Elvis movie, Luhrmann says, “Austin Butler did not do an impersonation. What he did was Austin Butler’s interpretation of the soul of Elvis Presley. An AI can impersonate, it can’t interpret.” As we’re parting, I ask him what he’d like to do, as a filmmaker, with AI. Turns out he has already incorporated it into his work—it was the tech he used to fade Butler’s face into Presley’s.